- Work-oriented learning and career guidance / Lifelong counseling

- Types and classification of work-based learning (WBL)

- Financing WBL

- Recommendations for implementing WBL

- Learning concepts, methodological and didactical approaches appropriate to WBL

- Learning concepts of work-based learning

- Methodological and didactical approaches appropriate to WBL

- Professional orientation / Lifelong guidance

- Guidance System in Germany

- Career education and vocational orientation in Germany

- Career Guidance and Counselling (CGC) by the FEA before working life in the transition from school to work

- Career guidance and counselling in working life by the Federal Employment Agency (FEA)

- Educational guidance services provided by municipalities

- Advice from chambers, business associations and social partners

- Private sector career development and coaching services, organisation consultancies

- Skills development advisory service for companies

- Example: Promotion of career orientation in inter-company and comparable vocational training institutions (BOP)

- Practice Example: Implementation of BOP in SBH

- Statements of partners

- Summary / Conclusions to reflections of the partners on the communicated questions regarding the application of WBL

- Wiki Terms

- Practical Tips

- Good Practices from other countries

- Examples of work-based-learning from local environment

Work-oriented learning and career guidance / Lifelong counseling #

- GPS WBL Intro 1

![]() Introductory Video

Introductory Video

Introduction to work-based learning (WBL) #

There is a multitude of perspectives when it comes to defining WBL, several approaches to its implementation and different terminology depending on the countries and on their educational contexts.

The rapid pace of transformation processes (e.g. digital / green) in industry and society raises attentions to new ways of vocational education and on-the-job training. This is rooted in the fundamental demand of enterprises for organization-wide competence development and planning in particular for re-/upskilling of workforces, and in turn recruiting competent workforce of the future.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, new ways of working have been emerging and could achieve certain levels of acceptance by industries and individuals. At the same time, new challenges are revealed concerning accelerated hybridization of work, digital and blended collaboration and eventually extended digital divide between white and blue collars. Notably, the latter did not benefit from advantages of remote work but had to deal with many challenges in presence. These challenges compound the demand on digital competences and raise attentions to effective measures for empowering human workforces on digitalized and technology-rich workplaces. In order to cope with the pace of change, vocational education institutions providing professional training programs for manufacturing enterprises need to critically rethink the as-is state, identify gaps based on new demands and thus improving educational concepts, models, and processes as well as underlying methods, tools and related infrastructure.

Despite the increasing industrial demands and urgency on innovative Work-Based Learning (WBL) and professional training, yet the potentials for introducing new, adapted, and tailored-made solutions remains unexhausted.

WBL merges theory and practice. It emphasizes that the workspace offers many opportunities for learning, i.e., obtaining knowledge, skills, and competences by experience. This is mainly due to its realistic, situated, complex and problem-oriented characters.

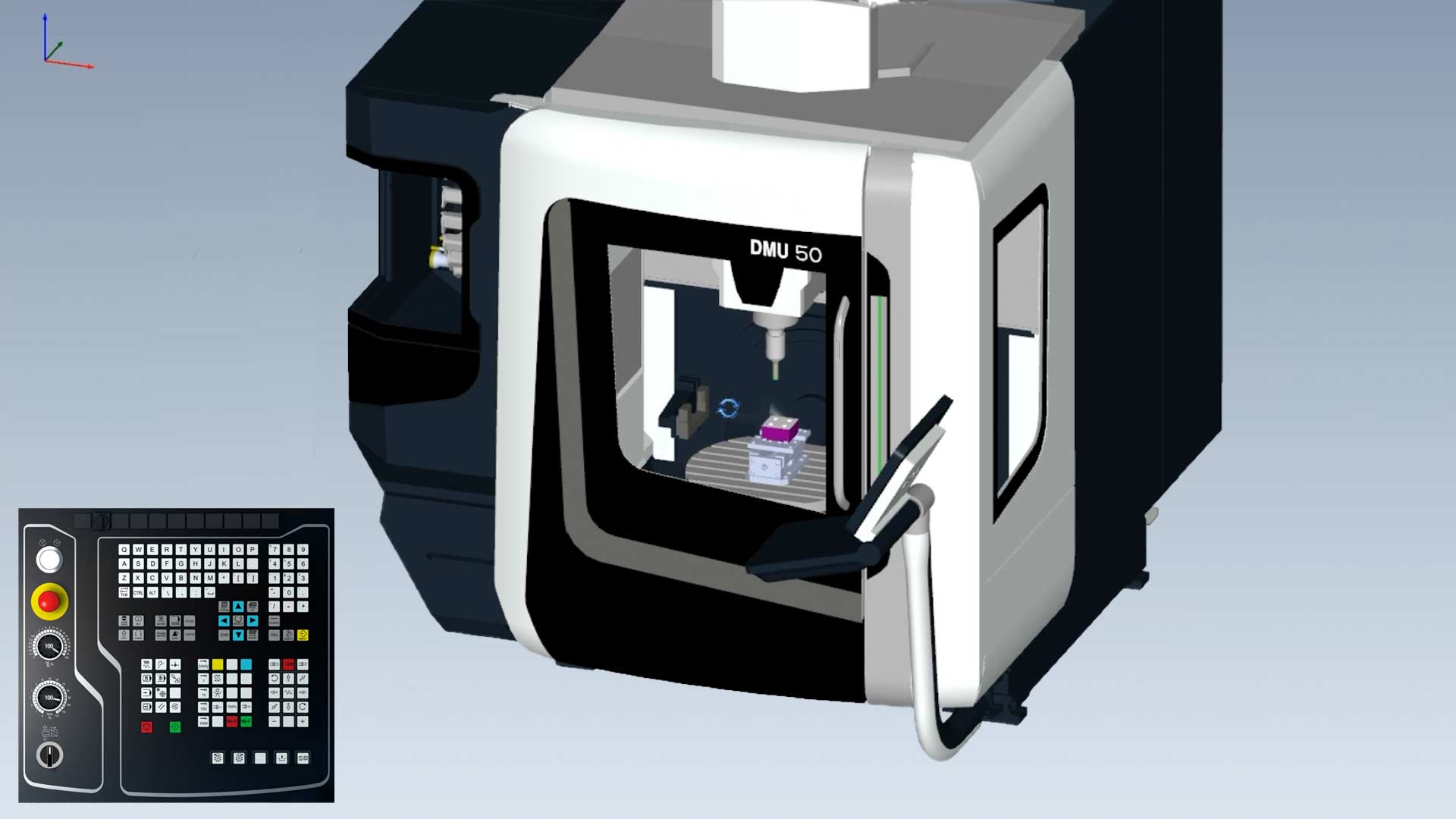

Considering the learning venue and workplace, WBL can be categorized into three types with certain coverage to the workplace (cf. Figure 1):

Work-oriented learning,

where learning mainly takes place in institutional settings such as schools, training centers or universities. Work processes, tasks and organization are simulated, e.g., e-learning, learning factories, off-the-job training courses.

Work-connected learning,

where learning venue and workplace are separated. Spatial and organizational connection between learning environment and workspace is present, e.g., learning at digital or physical twin next to the workplace, internships.

Work-integrated learning,

where learning venue and workplace are identical. The actual learning takes place at the workplace or in the work process, e.g., on-the-job training, traditional apprenticeship. (Nixdorf, S. et al. 2022)

Figure 1: Concept of work-based learning (Inspired by Dehnbostel & Schröder 2017)

Work-Oriented Learning

SIMULATION

ORGANIZATION

ACTUAL WORKSPACE

Work-Connected Learning

Work-Integrated Learning

The different perspectives on WBL are addressed by several relevant EU institutions in their studies and resources.

According to the European Centre for the Development of Vocational Training (Cedefop) Terminology of European education and training policy (Cedefop 2023), Work-Based Learning (WBL) is defined as an instructional model with well-defined learning objectives. It allows learners to acquire knowledge, know-how, information, values, skills and competences carrying out – and reflecting on – tasks:

- at the workplace – also known as workplace learning or in-company training – e.g. through internships/traineeships, apprenticeship, alternance training or company visits, job shadowing, etc.;

- in a simulated work environment, e.g. in workshops or laboratories in vocational education and training institutions, inter-company/social partner training centres.

The aim of work-based learning is to achieve specific learning objectives through practical instruction and participation in work activities under the guidance of experienced workers or trainers.

Types and classification of work-based learning (WBL) #

A joint – so called – Interagency Working Group – consisting of European Training Foundation (ETF), Cedefop, International Labor Organisation (ILO), Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) and United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation (UNESCO) dedicated to work-based learning, created in 2015, and produced a manual titled “Work-based learning and the Green Transition” (2022).

In this manual the following definition on WBL is given:

“(…) all forms of learning that takes place in a real work environment. It provides individuals with the skills needed to obtain and keep jobs and progress in their professional development. Apprenticeships, internships/traineeships and on-the-job training are the most common types of work-based learning.”

| Types of WBL mentioned | ETF & Inter-Agency WG on WBL definition | Cedefop Glossary definition |

| Apprenticeships | Provide occupational skills and typically lead to a recognised qualification.They combine learning in the workplace with school-based learning in a structured way. In most cases, apprenticeships last several years. Most often the apprentice is considered an employee and has a work contract and a salary. | Systematic, long-term training alternating periods at the workplace and in an education or training institution.It leads to recognised qualifications and is based on an agreement that defines rights and obligations of the apprenticeship, employer and, where appropriate, the VET institution. (…)

The German Dual System is an example of Apprenticeship. |

| Traineeships / Internships | Workplace training periods that complement formal or non-formal education and training programmes. They may last from a few days or weeks to months. They may or may not include a work contract and payment. | The term used by Cedefop for this type of WBL is Work Placement/Traineeship, described as:Period of time, usually forming part of an education or training programme spent in a company or organisation to get work experience. |

| On-the-job training | It takes place in the normal work environment. It is the most common type of work- based learning throughout an individual’s working life. | Cedefop does not include this type of WBL as term related to it. Nevertheless, it provides a definition of what it is:Training given in a real work environment. (…) may be combined with off-the-job training [training undertaken away from a normal work context, usually part of a whole training programme. |

Figure 1: Comparison between definitions provided by Cedefop and ETF & Inter-Agency Working Group on WBL of specific types of WBL

(Source: European Forum of Technical and Vocational Training (2023). Work based Learning Guide.)

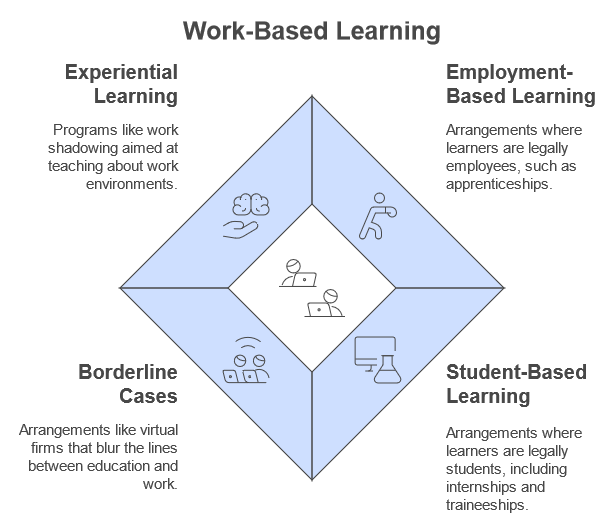

In summary, the following forms of work-based learning can be identified and named:

- arrangements in which the learner is legally an employee, such as formal apprenticeships, and in some cases alternance; in some cases informal apprenticeships may come under this heading;

- arrangements in which the learner is legally a student; these can be called by a number of names, including traineeships, internships, work placements and cooperative education;

- borderline cases such as virtual firms, training firms, or ‘real’ firms that are attached to and part of educational institutions;

- programmes such as work shadowing and work experience, the main aim of which is to teach the learner about work rather than to teach them to do work.

Figure 2: Classification of WBL types

According to the European Training Foundation (European Training Foundation. (2014) the differences between these are often not clear, as they can be quite similar. It is also important to be aware that wide variation can exist within each type.

When designing WBL-programmes to be focused on specific target groups, there are a number of questions that policy makers should ask themselves.

- What is the profile of the target group? For example: school drop-outs or graduates; individuals with special needs.

- What is the aim of the programme? For example, catch-up classes; integration into a mainstream vocational pathway; providing a fast track into the labour market; upskilling; retraining.

- What methods can be used to address the specific requirements of the target group? For example:

- pedagogical methods; flexibility of curricula; individualisation of learning pathways; partnerships with key stakeholders; funding mechanisms; appropriate training environments.

- Are there good practices that can be built on? Have similar programmes in the past or in other

- geographical regions led to particular successes, or have they had substitution effects between the target group and regular labour?

Apprenticeships

Alternance

Simulated workplaces

Traineeships

Learning about work

Vocational qualifications and skills

Work habits and employability

Career Choice

Unemployment and disadvantage

Figure 3: WBL – Choices related to purpose (Source: European Training Foundation 2014 )

Advantages and Disadvantages of Programmes that teach students about work

| Advantages |

|

| Disadvantages |

|

Figure 5 Advantages / Disadvantages of WBL (European Training Foundation. (2014)

Financing WBL #

Like all forms of education, specific types of costs must be taken into account for the different forms of WBL.

A proper understanding of costs is needed as a basis for budgeting and planning. There are three types of work-based learning programme costs: work-based costs; school-based costs; and costs involved in managing and steering programmes. These costs can be borne by companies, by individuals, and by governments. They can be incurred at the national, regional and local levels. Costs are influenced by the design features of programmes such as how much time is spent in the workplace, and by policy decisions such as how much assessment should be done. Overall costs are also influenced by the number of places offered by employers and the number of young people wanting places in programmes.

VET system costs

- Setting standards

- Inspection and supervision

- Assessment

- Counselling and guidance

- Research

- Administration

School-based costs

- Teachers’ salaries

- Teachers’ professional development

- Training equipment and tools

- Maintenance

- Communal services (electricity, water etc.)

- Learning materials

Work-based costs

- In-company trainers

- Trainers’ professional development

- Training equipment, tools

- Learning materials

- Learners’ wages/ allowances

- Learners’ insurance

- Learners’ transport

- (Inter-company training centres)

+ +

Figure 4: WBL- programme costs (Source: European Training Foundation (2018). Financing work-based learning as part of vocational education reform)

In an ideal world there is a simple model of how work-based learning is or should be financed. In this model:

- Governments meet all the costs of the school-based part of programmes.

- Employers meet all the costs of the training that takes place in firms.

- What learners are paid by firms reflects their productivity and rises as they become more productive.

- Total costs for the firm (wages plus training costs) are either less than learners’ productivity (so that the firm makes a profit, and the in-firm training is self-financing) or equal to learners’ productivity (so that the firm does not make a loss from taking part in the programme).

However, this ideal model is rarely achieved in practice.

- Some of the school-based costs can be met by employers – for example by donating equipment – or by individuals in the form of tuition fees.

- Governments adopt a range of methods to meet part of companies’ training costs – for example through direct grants, wage subsidies and taxation relief.

- When training in the firm is not organised effectively, apprentices’ or trainees’ productivity may never exceed the costs of training them.

- When learners are unpaid – for example in internships and work placement programmes – they may deliver productivity that is well in excess of the firm’s training costs.

These differences between the ideal model and the real world help to explain why the financing of work-based learning programmes can involve a wide range of mechanisms and policy choices to help bring the costs to firms, individuals and governments more closely into line with the benefits that each gains in order to achieve the principle policy objectives of work-based learning.

Models of financing WBL programmes

| The ideal model | Reality |

| Government meets all school-based costs.Employers meet all company-based costs.

Learners’ wages reflect their productivity over time. Learners’ wages plus company training costs are equal to or less than their productivity. |

Employers and learners also contribute to school-based costs.Governments subsidise employers’ training costs.

Learners wages are higher than their productivity OR unpaid trainees deliver productivity that exceeds company training costs. Learners’ wages plus company training costs exceed their productivity. |

Table 1: Financing WBL: Ideal model and reality (Source: European Training Foundation (2018). Financing work-based learning as part of vocational education reform)

With regard to the Erasmus project KA220 VET, some specific aspects of WBL in the area of learning about work are referred to below.

Programmes that try to teach students about work can be called work experience, work shadowing, enterprise visits or similar terms. Learning about work can help to improve transitions to work. They usually:

- involve quite brief periods in the workplace;

- are only quite small parts of the school or college programme: for example, they may be part of a single subject, or part of a career education programme, rather than being integrated with a complete course of study.

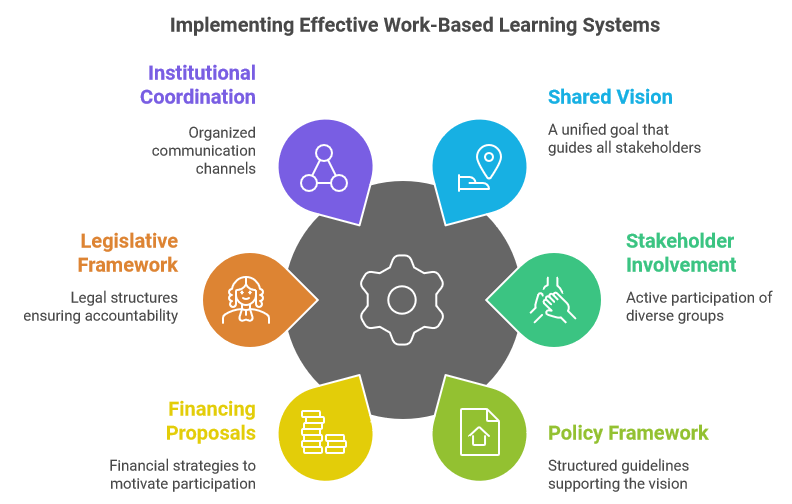

Recommendations for implementing WBL #

Following recommendations are based on lessons of countries that want to introduce, expand or reform work-based learning systems or programmes (Source: (European Training Foundation. (2014))

- Start with a shared vision, involve key stakeholders in developing it, and make sure that all key stakeholders are committed to it. This should include as a minimum all relevant government ministries and agencies, employer organisations, chambers (of commerce, trade, craft, agriculture, etc.), employee organisations and VET providers. Local and regional economic development bodies, parents, community organisations and non-governmental organisations are other stakeholders in many countries.

- Build a policy framework around this shared vision, and ensure that it has strong political support.

- Make sure that the framework gives strong ownership and control to the social partners over key parts of the new system or programme. This could include elements such as policy development, selecting participants, developing skill standards, developing the curriculum, assessment and certification, and quality assurance.

- Make sure that the framework includes proposals for financing (this may include wages, subsidies, taxes, industry levies, social security and insurance, and other similar factors) that will motivate both employers and learners to participate.

- Create a comprehensive legislative and regulatory framework to support the policy framework and vision. Make sure that the legislative and regulatory framework clearly sets out the areas of responsibility of each of the key stakeholders.

- Create channels for institutional coordination and communication to support the framework, such as national VET councils, industry-sector councils and regional councils.

- Make sure that new systems or programmes do not compete (for participants, for employer places, or for the involvement of social partners) with existing systems or programmes of work-based learning. If there is more than one type of work-based learning programme (for example, apprenticeships and internships), make sure that they target different occupations, industries or individuals.

- Take a long-term view. Unless there exists a strong institutional tradition that is likely to support work-based learning programmes and systems, begin with pilot programmes. Evaluate and learn from these, share what has been learned with key stakeholders, and modify and improve what is being done as a result of experience and evaluations.

- Use international partnerships to help build the system if the necessary knowledge and experience is not available nationally.

- Put a great deal of effort into building the tools that are needed to support new programmes and

- systems, including competency standards, curricula, skill lists for enterprises and students, and

- assessment tools.

- Put a great deal of effort into developing the knowledge and skills of the people who will need to make the system or programme work at the local level: enterprise tutors or trainers, vocational teachers, curriculum developers and social partners.

- Actively market and communicate the new system or programmes to all key stakeholders. Do this at the local and regional levels, not just at the national level.

Figure 6: Elements for implementation of WBL

Learning concepts, methodological and didactical approaches appropriate to WBL #

As mentioned above, the term “work-based learning” is semantically broad and has many different meanings. Depending on its relation to in-company work, work-related learning can differ widely. Three variants of work-based and work-related learning can be distinguished from the criterion of the relationship between the place of learning and the place of work. (Dehnbostel 2009, 2631 ff.)

When discussing aspects of learning organization and didactic-methodological criteria, five types of work-based learning can be distinguished and attributed to different organizational concepts of learning and organizational forms of learning. Individual concepts or shapes can be assigned to several models if they are designed differently.

| Models of work-related learning… | Work-related forms of learning organization |

| (1)…through active participation in real work activities(work-integrated learning) | Learning on the job; communities of practice (colleagues); traditional apprenticeship; adaptation training |

| (2)…through companionship and instruction at work place(work-integrated learning) | Coaching; mentoring; learning facilitation; instruction; CoP (e.g. internet forum); initial skills training; online communities |

| (3)…through combination of informal and formal learning(work-integrated and work-connected learning) | Structured learning on the job; blended-learning; E-learning (e.g. virtual work and learning space); learning bay; quality circle; coaching; work- and Learning Task |

| (4)…through in-company observation and exploration(work-connected and work-integrated learning) | R&D-based internship during program in higher education; in-company internship; pre-vocational program; benchmarking |

| (5)…through simulation of work organization, tasks, and processes in institutional setting(work-oriented leaning) | Learn- and working tasks; learning fields; learning factory/office/bakery/restaurant/hotel etc.; project learning; E-learning |

Figure 7: Models of work-based and work-related learning (Dehnbostel 2007)

Learning concepts of work-based learning #

The learning concepts for learning in and at work as well as for learning via work all aim at action-orientation and self-direction of the learner. They are shaped very differently when implementing methodical and didactic approaches. In work-integrated forms of learning such as learning on the job and communities of practice, a primarily informal learning takes place in the absence of didactically structured learning organization. Work-connected and work-oriented models are essentially related to formal learning and are intentionally structured by didactic-methodological methods.

Situated Learning

Situated Learning aims at action-learning in real work and life situations (Lave & Wenger 1991, Lave 1993). The situation and the social context characterize situated learning, which at the same time means that this learning is not functionally reduced, but is a form of acculturation, of growing into the learning and working culture. In contrast to relevant cognitivist learning concepts, the learning process is embedded in the respective conditions of original and surrounding situations and cannot be separated from them. Not only knowledge and skills are passed on through this learning, but habits, attitudes and values. In a broad understanding, the concept of situated learning is the realization of a theory of social learning.

Situated learning is a process of continuous enculturation into a social group with its specific objectives, competences, internal structures and rules. The process of acculturation, becoming a full-fledged member, involves not only the acquisition of the relevant competencies dominated by the group, but also the acquisition of typical cultural practices and the formation of a group identity

The concept of situational learning is based on the social context of a community of practice, a meaningful and sustainable practice, as well as the relevance of one’s own actions. The affiliation to a group is socially and individually integrating and supportive. Learning and competence development take place in a common social space and embraces all members of the group.

This is especially the case for learning at the workplace: learning is done interactively with binding reference to work tasks and the respective subtasks of organization, planning and disposition. Attitudes and values are acquired in the group and within the work organization through socialization and mutual learning processes. Such an understanding of learning requires a different picture of learning than institutionalized formal learning. It is an experiential and informal learning that through integration into the social group and participation in their intentional actions eventually leads to learning outcomes and competences.

Self-directed Learning

Self-directed learning is the independent and self-determined control of learning processes. The learners determine the objectives and contents of the learning process in a certain framework, as well as the methods and tools for the regulation of learning, largely independently. However, the scope of the action or the superordinate structural classification of the relevant learning situation in work processes is predetermined under fixed criteria. With regard to the framework and the environment, self-directed learning is not autonomous learning, but goal-oriented selection and determination of learning possibilities and learning paths.

This also addresses the crucial difference between self-directed and self-organized learning. In the case of self-organized learning, the institutional and organizational framework of learning is determined by the learner and is not determined from outside, as in self-directed learning. However, learning in work processes usually takes place in working situations, which are not specifically designed for learning. They are determined, however, by their objectives and higher organizational structures. At the same time, they enable independent and self-directed learning within the given framework, particularly reflexive learning based on experiences. Self-directed can refer to both an individual and a group.

Independent of learning theorems, the individual´s self-direction is a prerequisite for participatory and networked working forms in restructured work organizations. The design of newly acquired handling and disposition margins, the implementation of continuous improvement processes, the application of integrated quality assurance procedures as well as the fulfilment of target agreements are increasingly self-directed. Such self-directed processes are the consequence of decentralization and de-hierarchization in new work organizations. They are characteristic of modern work processes and at the same time inseparable from informal learning processes.

In this respect, the individual’s self-direction in the work process and the resultant learning undoubtedly subordinate purposes and criteria, based on economic intentions, competitiveness and the corresponding forms of organization and qualification. Self-direction has become an important business factor in modern companies. From the individual´s perspective, there are self-directed action and learning orientations instead of instructional and hierarchical thinking, behavioural and orientation patterns. Processes and developments are made possible which take up real experiences and subjective interests more strongly and which correspond to a differentiation of educational paths and life patterns. To what extent these developments in the work can actually take place and be self-controlled does not exert itself primarily in an increased responsibility and the burden lies on the respective working conditions and working culture.

Reflexive Learning

Reflexive learning, as well as self-directed learning, embraces the changing learning and working conditions in modern work processes and the renaissance of learning at work. It is based on real work and action situations, and their consideration in work-related learning concepts has a historical forerunner, which focus on experience.

Reflexive learning is a form of learning through understanding and conscious reflection of experiences. The underlying experiences are the result of sensory, emotional, social and cognitive perceptions. Intensive reflexive learning takes place in the work when the work processes are enriched by problems, challenges and uncertainties for the worker. The problems and its solutions are being reflected upon, which leads to the generation of knowledge.

Structural reflexivity aims to raise awareness of the rules and resources and the structures and social conditions of existence of the actors themselves. In self-reflexivity self-determination takes the place of the former heteronomous determination of the actors i.e. acting worker. Self-reflexivity, therefore, describes the capability of self-perception and the reflection of the actors over themselves. This ability to reflect and thus to detach from the surrounding structures is determined by the biography and the steps of formation and development contained in it, but influences this in turn in a retroactive process.

Self-determination and personality formation are inseparably connected with the ability to self-reflect and the recognition of social-enterprise processes. In actual work, reflexivity means, therefore, to reflect on work structures as well as about oneself, and connect with the preparation, execution and evaluation of work tasks. The tabular overview summarizes the dual reflexivity.

| Mode of reflexivity | Reflexivity in and about work |

| Structural reflexivity | Questioning and shaping work, working environments and work structures |

| Self-reflexivity | Reflection on your own competencies, shaping your own competence development |

Figure 8: Dual Reflexivity (Dehnbostel 2007)

In modern work processes, experiences are no longer made in the same way as in conventional work. The sensory feedback of work on the subject is changed, partly by the use of information and communication technologies. Above all, work experiences, which are mainly perceived through seeing, hearing and feeling are considerably limited of their things and services through automation, the employment of handling devices, diagnostic systems and the internet.

The digitalization of the working world continues at a rapid pace, which is emphasized through the concept of Industry 4.0. Reflexive learning does not refer to the reflexive processing of sensory experiences, but to an extension of the external experiences beyond the conventional sense through mental, cognitive, emotional and interactive digital processes. The digital working world connects the physical to the virtual working world and requires reflexive learning, especially in this phase of technological transition. The reflexive processing of increasingly digitalized experiences and thus reflexive learning itself seem equally relevant for all variants and models of work-related and work-based learning.

Methodological and didactical approaches appropriate to WBL #

Effective pedagogical approaches for work-based learning include:

- Experiential learning:

- Providing hands-on experiences in real work environments

- Allowing students to apply classroom knowledge to practical situations

- Reflective practices:

- Encouraging students to reflect on their experiences

- Using techniques like journaling or group discussions to analyze and learn from work activities

- Project-based learning:

- Assigning real-world projects that align with workplace tasks

- Allowing students to work on complex, multi-step assignments

- Mentoring and coaching:

- Pairing students with experienced professionals for guidance

- Providing ongoing feedback and support

- Problem-based learning:

- Presenting students with authentic workplace challenges to solve

- Developing critical thinking and problem-solving skills

- Simulations and role-playing:

- Creating realistic workplace scenarios for practice

- Allowing students to take on different roles and perspectives

- Collaborative learning:

- Encouraging teamwork on projects

- Developing communication and interpersonal skills

- Technology-enhanced learning:

- Using online platforms, virtual reality, or other digital tools to enhance experiences

- Providing access to resources and experts remotely

- Assessment-driven learning:

- Using frequent assessments to gauge skill development

- Providing opportunities to demonstrate mastery through portfolios or presentations

- Interdisciplinary approaches:

- Integrating knowledge from multiple subject areas

- Helping students see connections between academic concepts and workplace applications

The key is to use a variety of interactive, hands-on methods that closely mirror real workplace situations and allow for application of knowledge, reflection, and skill development. Effective work-based learning pedagogy should be tailored to specific industry needs and student learning objectives.

Detailed descriptions of a broad collection of macro and micro methods can be found in the “Handbook on Blended learning concepts, teaching and learning methods for enhancing ICT skills for women” – which is part of the Erasmus project “Entrepreneurial Women In ICT – Enhancing ICT Skills to Bridge Digital Divide”.

Depending from the specific target groups and objectives of competence development for the specific target group to be addressed in work-based learning settings appropriate methods could be selected, applied and adapted to the specific situations.

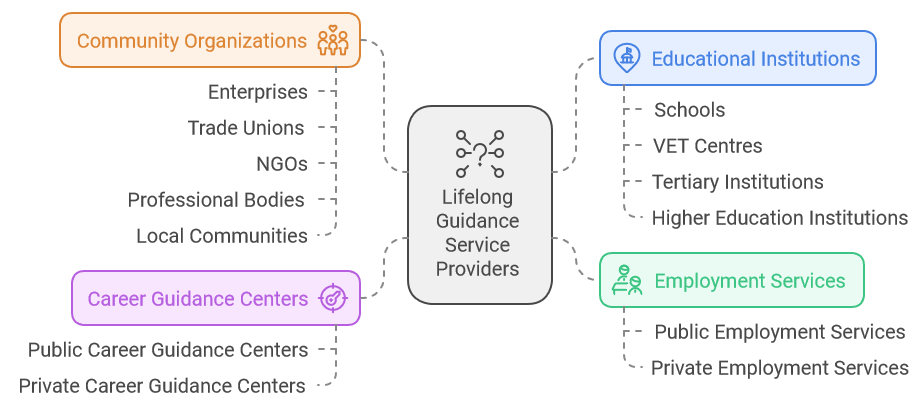

Professional orientation / Lifelong guidance #

The Cedefop Glossary (Cedefop 2023) describes professional orientation in the sense of lifelong guidance as a continuous process that enables an individual, at any age and at any stage of life, to identify his/her capacities, competences and interests, to make well-informed educational, training and occupational decisions, and to manage his/her life path in learning, work and other settings in which those capacities and competences are learned and used.

In more detail, it is explained in the Cedefop Glossary:

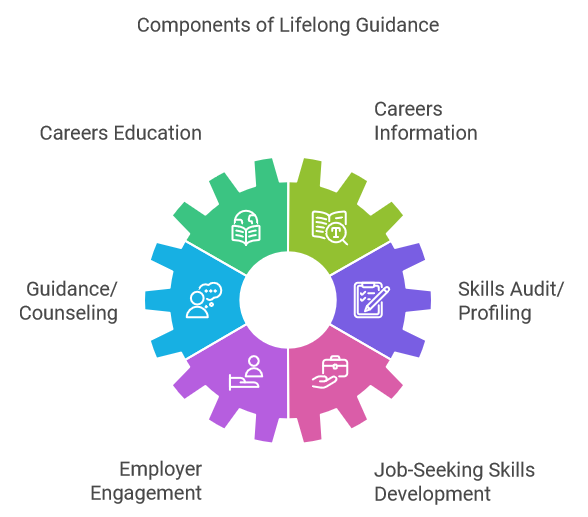

- Lifelong guidance covers a range of individual and collective, formal or non-formal career development activities such as information-giving, counselling, competence assessment / skills audit / competence profiling, support, and the development of decision-making and career management skills through career education;

- it can be undertaken throughout life, from school and throughout both working and non-working life;

- lifelong guidance services can be provided face-to-face, remotely (e-mail, chat) or in a blended mode in a wide range of settings:

- schools and VET centres;

- tertiary and higher education institutions;

- public and private employment services;

- public and private career guidance centres;

- enterprises, trade unions, NGOs and professional bodies as well as in local communities;

Figure 9: Lifelong Guidance Service Providers

- lifelong guidance can be seen as occurring at specific transition points, as a subset of lifelong guidance that involves capacity building; it enables an individual to reflect on his/her ambitions, interests, qualifications, skills and talents through learning – and to relate this knowledge about who s/he is to who s/he might become in life and work;

- lifelong guidance includes provision of:

- careers education;

- careers information;

- individual and group guidance/counselling;

- skills audit / competence profiling and psychometric testing;

- engagement with employers;

- development of skills needed for job seeking and self-employment.

Figure 10: Components of Lifelong Guidance

Guidance System in Germany #

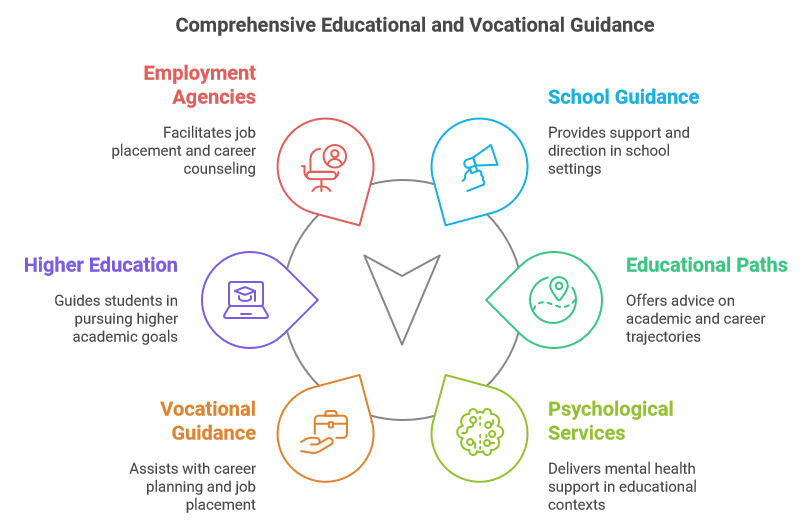

The German Guidance system provides in principle access to educational and career guidance services for all citizens at any stage of their lives – whether they are in education or training, employed, unemployed or looking for continuing education.

The provision of career guidance is traditionally based on the distinction between educational guidance and vocational guidance in the vocational training and employment sector.

Educational guidance comprises

- School Guidance and counselling,

- Guidance on educational paths,

- School Psychological Service,

- Vocational and Career Guidance by the Federal Employment Agency (FEA),

- Higher Education (HE) counselling services.

Vocational guidance includes

- Placement and counselling in the local Employment Agencies (EA)/Job Centre,

- Career guidance in the FEA,

- Municipal educational guidance / Adult education centres,

- Career Guidance in the chambers (eg. Industry and Commerce, Crafts) and

- Guidance by providers of further training.

Figure 11: Educational and vocational guidance – different focus and target groups

Policy

The structure of guidance provision reflects the German education and employment system with its shared responsibilities between the Federal Government, the federal states and the municipalities. A key player in the implementation of guidance provision is the Federal Employment Agency (FEA) with its more than 150 local Employment Agencies (EA) and career information centres (BIZ). In addition to Federal institutions, the local municipalities play an important role by providing guidance services either through Adult Education Centres or their social welfare services.

Further, the National Guidance Forum for Education, Career and Employment – an independent network of politically responsible institutions, organisations and experts – promotes the professionalism and quality delivery of guidance in the education and employment sector in Germany. Along with members of the Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF), the Standing Conference of the Ministers of Education and Cultural Affairs (KMK) and the FEA, it also contributes to a strategy of Lifelong Learning in Germany in which a coherent system of lifelong guidance is an integral component

In the context of a steadily changing world of work, reference should be made to the National Skills Strategy (Nationale Weiterbildungsstrategie) which was developed by the Federal Ministry of Labour and Social Affairs and the Federal Ministry of Education and Research, together with the social partners, the Länder, the Chambers of Industry and Commerce as well as Crafts and the FEA. It was officially adopted on 12 June 2019 and is based on the Skills Development Opportunities Act (Qualifizierungschancengesetz), which already contains a binding right to counselling on continuing education and training by the FEA. In future, the focus will no longer be on formal qualifications alone, but also on individual skills. The aim is to help all current and future employees to maintain and adapt their qualifications and skills in a changing world of work and to enable them to up-skill or to change careers.

Services and Practices

The FEA is mandated by law to offer career guidance for young people and adults. This is non-commercial and geared to the needs of those seeking advice, with the aim of broadening the spectrum of career choices. Besides the FEA, there are other private guidance service institutes.

General education institutes are responsible for providing guidance services in schools which are offered throughout entire school education. Specially trained teachers, social workers, school psychologists and cooperating vocational guidance practitioners from the FEA provide counselling in school.

In higher education (HE), central counselling services as well as faculty-based expert guidance are provided to students and applicants to inform on all study-related topics such as choosing a university, a field of study, subjects, and examination preparation. Career Services within the HE institutions offer support in the transition from university to employment.

Guidance in the fields of employment, continuing education and avoiding unemployment is provided by the FEA free-of-charge to all citizens. This is mainly carried out by placement officers, who are usually trained counsellors and who assess skills and competences of their clients before defining an action plan for the latter. Youth Employment Agencies are responsible for the counselling and integration needs of young people under 25 in Germany. In the Youth Employment Agencies, counsellors from the employment agencies, job centres and youth welfare organisations work together and offer coordinated and individual support for young people in their transition to training and work. Further, most municipalities maintain adult education centres. They provide both general education as well as continuing vocational education and training (CVET).

Besides the FEA and municipalities, the chambers of commerce, industrial federations and social partners provide services for information related to VET and CVET to all stakeholders. Guidance practitioners in the chambers, e.g. give advice on different topics concerning apprenticeship in the dual system such as information on the course of the apprenticeship, youth protection in the workplace etc.

Furthermore, trade unions provide career guidance to their members on questions related to further training while management consultants, private career guidance practitioners and a growing number of non-profit organisations offer guidance services within the private sector.

Finally, a variety of guidance services is offered to special targets groups, among others people with disabilities, disadvantaged youth and people with a migrant background.

Training

There is no legal regulation of the qualifications, training and professional status of career guidance practitioners and counsellors in Germany. Each sector or provider of guidance defines its own requirements – normally a higher education degree (Bachelor or Master) and some additional further training are a prerequisite.

The FEA runs its own University of Applied Labour Services (UALS) where career counsellors study a three-year multi-disciplinary Bachelor programme which closely links theory to practice in the Employment Agencies. The fields of study include public management, employer-oriented work incentive counselling, employee integration and social security. Further, the UALS offers a Master Programme (5 semesters) focusing on labour market-oriented guidance. In addition to the study programme at the UALS, there are in-house training and further education for staff in local Employment Agencies and Job Centres who have various academic backgrounds and move from other posts to career guidance.

(Euroguidance.2024)

Figure 12: German Career Guidance Services – Actors and Responsibilities (Source: National Guidance Forum. 2022)

Career education and vocational orientation in Germany #

Career education and vocational orientation to prepare students for their career choices is an integral part of the curricula (in all Federal States) in both lower and upper secondary schools in all Federal States, based among other things on corresponding agreements between the Standing Conference of the Ministers of Education and Cultural Affairs (KMK) and the FEA. The aim is to prepare students for the world of work by improving their career management skills and their ability to search for and use relevant career information and make decisions. In some countries, this is offered as part of a separate subject, variously called “working life lesson”, or “work-economy-technology”, and the like. However, career education can also be integrated into other subjects (e.g. social studies or business and law). Often, additional extracurricular activities are offered in cooperation with local employers, for example company visits and internships. Class visits to the career information centre (BIZ) of the local EA are also an integral part of school-based career orientation. Many schools use a career choice passport, based on a portfolio approach, which enables students to document their educational and career-related experiences and competencies (https://www.berufswahlpass.de/).

Throughout Germany, partnerships between schools and the world of work are supported by regional “school-business working groups” (Arbeitskreis Schule-Wirtschaft). In addition to internship programmes for teachers and students, continuing education for teachers, and other labour market-related offerings, these working groups support “student companies” or establish partnership agreements between schools and local enterprises to provide students with hands-on experience (https://www.schulewirtschaft.de/).

Career Guidance and Counselling (CGC) by the FEA before working life in the transition from school to work #

In Germany, in addition to schools, the local EAs are primarily responsible for career guidance and vocational counselling for pupils and students. As a rule, these services begin around 2 years before pupils leave school, i.e. in grade 7 or 8 (grade 9 in Gymnasium).

This practice, which is unusual in comparison to other EU countries, is based on the traditionally high importance of the dual apprenticeship training system for the vocational qualification of young people.

The choice of an apprenticeship occupation and placement in a training company can be more successful if it is supported by counsellors who have experience in the labour market and direct contacts with training companies and employers. For this reason, the EAs offer a combined service of career guidance, individual counselling, training placement and, if necessary, financial support. This however does not mean that career counselling by the EAs focuses exclusively on placement in a dual vocational training programme, but rather that it provides neutral and open-ended counselling.

The EA’s career orientation measures for pupils include a wide range of events at school, at the Career Information Centre (BIZ) and at training fairs, as well as support in the search for an internship, organising workshops and seminars on career choice topics or support in preparing application documents, and much more.

Individual face-to-face counselling usually takes place as a scheduled personal counselling session on the premises of the local EA, but it may also be conducted by telephone and increasingly also by video communication. In addition, the counsellors offer fixed office hours in schools and non-scheduled brief consultations in the BIZ.

If it proves necessary in the counselling process, the EA’s specialist services (occupational psychology, medical service and technical advisory service) can be involved. They conduct psychological assessments and tests or prepare medical reports to clarify the cognitive, psychological and physical capacity and suitability for certain occupations and trainings. These specialist services are called in on the recommendation of the career counsellors, especially for certain target groups (e.g. people with disabilities and disadvantaged young people).

The counselling services offered by the EA are supplemented by financial support instruments for training seekers and trainees (e.g. through vocational preparation courses, introductory training, training-accompanying assistance, assisted training). Disadvantaged youths and young people with disabilities can undergo vocational training in extra-company establishments or in special vocational training centres.

A wide variety of print and online media on topics such as occupations, careers, training and study opportunities, as well as digital self-exploration tools (e.g. “Check-U” and “NewPlan”, “planet-beruf” and “abi”) and labour market information complement the FEA’s range of services (Chart 2). They are available in the BIZ and on the Internet, and are also distributed to schools.

Cooperation between schools and the career guidance services of the FEA is governed by an official agreement between the FEA and the Standing Conference of the Ministers of Education and Cultural Affairs of the Länder (KMK 2004/2017) and supplementary agreements at Federal State level. In alignment with teachers, career counsellors from the EA can participate in career education classes, hold office hours at schools, and supervise school classes visiting the BIZ.

In addition to cooperating with schools, the EA’s vocational guidance services work closely with chambers of industry, commerce and crafts, employers associations, trade unions, educational institutions and other public institutions such as the youth and social welfare authorities, and non-profit organizations supporting special target groups.

Since 2013, joint contact points have been established at the local/regional level, so-called “Youth Employment Agencies” (Jugendberufsagentur), which serve to improve local networking and more effective cooperation between the EA and Jobcentres with the municipalities and youth welfare agencies as well as with schools and other stakeholders in the field of transition from school to work. The aim of the Youth Employment Agencies is to offer young people seeking advice a “one stop shop” where they can find services from the various guidance and counselling providers as well as financial support for vocational training “under a single roof”. This is intended to achieve more comprehensive support and smoother social and vocational integration of young people (BA 2018; https://servicestelle-jba.de).

(Source: National Guidance Forum. 2022)

Career guidance and counselling in working life by the Federal Employment Agency (FEA) #

In addition to job placement services and financial support for the unemployed and those threatened with unemployment, the local EAs are legally obliged to offer CGC (including advice for CET) as a free public service to all citizens regardless of age, education, living and working situation (SGB III, §§ 29–33, 38). As part of the National Skills Strategy adopted by the Federal Government in 2019 (BMBF 2019a), the FEA’s guidance mandate was strengthened and expanded, specified by the Skills Development Opportunities Act to include the entitlement of employees to CET guidance by the EA. The goal of this expanded counselling mandate is, among other things, to attract more people, especially the low-skilled, to participate in CET in order to meet the increasing skilled labour shortage, caused by demographic and structural changes and the digital transformation in the economy, and to maintain the individual employability of employees.

With the Lifelong Guidance Concept and its differentiated range of orientation and counselling services, the FEA aims to support all people participating or wishing to participate in working life in their professional development and in realising their goals in a targeted and tailored manner. To this end, it provides a wide range of services, from career guidance events, individual counselling, potential analysis and skills assessment, to job application assistance and financial support for professional integration, including various online services for self-information about education, careers and the labour market, and digital tools for self-exploration (“Check U” and “NewPlan”;).

Placement and counselling services for unemployed persons and job seekers are usually provided by placement officers working on the basis of the FEA’s counselling concept. People with an extended need for guidance and counselling are advised by career counsellors who are specially qualified for the Lifelong Guidance Concept (LBB).

The Employment Agency is legally obliged to provide vocational guidance for registered jobseekers immediately after registration (SGB III § 38). Based on a strength/weakness analysis (profiling), the skills and competencies as well as the suitability for certain jobs or for an intended qualification are determined. The next steps and obligations of the unemployed person and the placement officer are specified in an integration agreement. If occupational integration requires further training or other measures, this is also documented in the integration agreement and must be implemented accordingly.

Unemployed persons as well as employees can obtain a voucher for further vocational training or retraining from the EA if this is necessary to improve their chances on the labour market (SGB III, § 81). Getting a voucher requires a consultation at the EA about the personal circumstances, motivation and suitability of the applicant as well as the approval of the vocational goal being pursued. Since the EAs may not recommend a specific training provider or course, the holders of a voucher must choose an accredited provider and course themselves either through the FEA’s nationwide database KURSNET or with the help of other CET databases or guidance providers.

Since 2005, the introduction of the Social Code II (merging of unemployment assistance and social assistance) into a basic benefit (Grundsicherung) for employable persons entitled to receive benefits has brought about fundamental legal changes for the vocational integration of long-term unemployed persons. This applies to all persons who have been unemployed for more than twelve months and receive basic benefits. In accordance with the principle of “support and demand”, participation in vocational counselling is also mandatory for this group of people. Counselling and support for the long-term unemployed under Social Code II is provided by the Jobcentres, which are either run jointly by the local EA and the municipality or by the municipality itself.

Long-term unemployed people receive comprehensive support at the Jobcentres. This includes not only job placement and advice on career perspectives and training opportunities as well as the promotion of integration measures, but also a consideration of the individuals overall life situation, including their family situation. Unemployed young people under the age of 25 are supported in a separate organisational unit (Team U 25) or – if such a facility is available locally – in the Youth Employment Agency.

Educational guidance services provided by municipalities #

A large part of the public guidance services for adults outside the EA are supported and organised by the municipalities or counties and are usually funded by the respective Federal State laws and their funding programmes.

Most municipalities maintain adult education centres (Volkshochschulen), which offer both general education and vocational training. Their regular tasks include providing information and advice on their own courses as well as learning guidance for participants. Increasingly, many adult education centres also offer educational guidance and counselling independent of their own course offerings. These counselling services are usually provided by the lecturers in addition to their teaching duties, but increasingly also by professionally trained, full-time educational counsellors.

However, more and more municipalities also maintain independent, neutral educational counselling centres, some of which are initiated and funded by the Federal Government or through state programmes and are open to everyone, regardless of age, life situation, age group, and employment status. The target groups for municipal educational counselling services include students, trainees, employed and unemployed people, people returning to work, and people with a migration background and refugee experience. It is also not uncommon for people belonging to the clientele of the Employment Agencies to ask for career guidance in municipal guidance centres, if they wish to get advice independent of legal or administrative restrictions and possible financial sanctions. The municipal guidance and counselling landscape is correspondingly diverse, heterogeneous and sometimes confusing. With its programmes “Transfer Initiative Municipal Educational Management” and “Education Municipalities” (Bildungskommunen), the Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) supports coordination and networking in the municipal educational landscapes, including the activities for municipal educational guidance.

Advice from chambers, business associations and social partners #

Chambers of commerce and industry, chambers of crafts and trades, social partners (trade unions and employers’ associations) and numerous other business associations and business training organisations also offer advice on vocational education and training. Some of their advisory services are also aimed at pupils, trainees and students, but they are primarily designed for employed or self-employed persons and for companies. However, there are no data on the scope and intensity of these advisory services. Face-to-face services are supplemented by various online services, such as regional or industry-specific databases on continuing education courses or online tools for self-assessment and skills assessment.

Supporting and controlling in-company apprenticeship training by providing information and advice is a statutory obligation of the chambers and other bodies responsible for vocational training (“training advice” according to the Vocational Training Act § 76/Handicraft Regulation Act § 41a). Training advisors at the chambers address not only the trainees, but also their parents or legal guardians and vocational school teachers, companies, trainers, works councils and youth representatives. This usually involves the training itself, examinations, the training contract with the employer and regulations on youth employment protection. If they experience difficulties at vocational school or problems at work, trainees also get support from the chambers’ training advisor.

Employed persons can obtain advice from the chambers, in particular on questions of further vocational training or setting up a business (e.g. https://wis.ihk.de/ihre-ihk/ihk-weiterbildungsberater.html or www.karriereportal-handwerk.de ). In addition, the chambers offer their member companies advice on skills development and recruitment.

Trade unions also offer their members and employees advice on job-related training. They support and advise their members, regardless of whether they are employed or unemployed. This is often done by works councils or shop stewards. A few years ago, shop stewards were trained as “training coaches” or “learning mentors” in pilot projects, but these models were not implemented across the board. Within the framework of the National Skills Strategy, the German Trade Union Confederation and some individual trade unions have now announced that they will train works councils and shop stewards as further training mentors in order to provide a low-threshold advisory service to encourage low skilled workers in particular to take part in continuing education.

Private sector career development and coaching services, organisation consultancies #

In addition to the public guidance provision and services provided by professional guidance associations and non-profit organisations, there have always been private-sector offerings from commercial education providers, freelance career counsellors or coaches, and corporate and organisational consulting firms. This private market has expanded rapidly since the abolition of the FEA’s career counselling and placement monopoly in 1998.

The services offered by the private sector are diverse and often highly specialised, and are aimed at groups of people with specific concerns and guidance needs – such as, for example, high school graduates in their choice of studies or training, counselling for persons unsure whether they are in the right programme of study or dropouts, start-ups, professional reorientation, and out- or new placement consulting for departing (older) managers, integration counselling for people with a (current) migration or refugee background. Occasionally, there are also professional counselling offers that are close to clinical-therapeutic areas of work, for example in the context of burnout prevention due to psychologically and physically stressful work situations. The boundaries between career counselling, coaching and psycho-social counselling and therapy or organisational consulting are often blurred, and many providers are active in several of these fields.

Generally, private-sector counselling services are fee-based for clients, unless they are provided on behalf of an employer or the local EA, which then pays for the costs. The price range for private counselling services is considerable.

Overall, the private market has been little regulated. If private-sector CGC services are funded by the public sector, quality testing is usually a prerequisite for contracting them. For labour market services funded under SGB III or SGB II, certification is required according to the “Accreditation and Licensing Ordinance for Labour Market Services” (AZAV; § 184 SGB III). Beyond that, there are no legal regulations for private CGC with the exception of § 288a SGB III, according to which the local EA is authorised to “prohibit career counsellors from carrying out this activity in whole or in part, if this is necessary for the protection of those seeking advice”.

Freelance counsellors and private career professionals are mostly organised in professional associations and usually follow their, sometimes quite demanding, licensing requirements and quality standards. There is no reliable data on the size of this private market, with the exception of membership figures published by some associations.

Skills development advisory service for companies #

Skills development advisory services support companies in determining the skills and qualification needs of their employees as well as in developing and implementing appropriate further education and training programmes. It focuses particularly on small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). They often lack the resources to assess the competency development needs of their workforce in the course of their company’s development (e.g. through innovations, digitalisation, demographic change, and the demand for skilled labour) and to develop a tailored human resource development and skills strategy. The aim is to make companies fit for the systematic and future-oriented management of their corporate learning processes and to make them aware of the necessity of lifelong learning, motivating them to invest more than before in the qualification of their workforce.

Skills development advisory service is mostly offered by business associations, chambers of commerce and industry, chambers of handicrafts, associations of social partners, universities and a large number of private and semi-private consultancies. The Federal Government and some state governments support various programmes and activities in this area. The OECD report on continuing education in Germany contains an overview of current support programmes and activities.

The FEA also offers a comprehensive skills development advisory service free of charge. Providing advice to employers and companies on issues such as recruitment and training is one of the EA’s statutory tasks (labour market advice, SGB III § 34). In order to be able to provide competent qualification advice, employees in the FEA’s Employer Service have been specially trained for this task.

Federal and state programmes to promote educational and career guidance

As part of the strategy for lifelong learning, the Federal and the State Governments support various initiatives and projects for (further) educational guidance with a large number of temporary programmes. Many of these programmes are aimed at supporting socially disadvantaged groups with special counselling and assistance needs.

Example: Promotion of career orientation in inter-company and comparable vocational training institutions (BOP) #

Promotion of Career orientation in inter-company and comparable vocational training institutions (Förderung der Berufsorientierung in überbetrieblichen und vergleichbaren Berufsbildungsstätten /BOP)

The program is funded by the Federal Ministry of Education and Research. ((https://www.berufsorientierungsprogramm.de/bop )

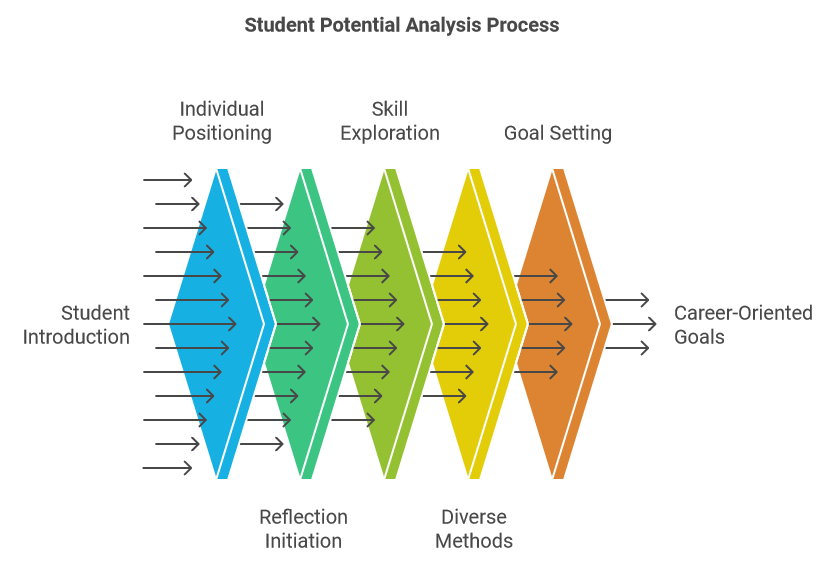

The career orientation program is aimed at students from seventh grade onwards. First, they explore their strengths in a potential analysis, then they try out various career fields in the practice-oriented career orientation (BO) days. The BOP is inclusive because it responds to a wide range of individual needs and requirements. The pedagogical approach and the instruments of the career orientation program Potential Analysis and practice-oriented BO days form the first links in the nationwide educational chains initiative, which aims to enable young people in Germany to make a smooth transition from school to work.

Instrument 1: Exploring strengths in the potential analysis

In the potential analysis, students explore their strengths. The potential analysis draws the young people’s attention to their own talents, strengths and interests before they try out specific professional activities during the practice-oriented BO days. The potential analysis does not commit the young people to a specific direction but opens their eyes to possibilities. The potential analysis is a balanced mix of tasks with practical individual or group tasks and a reflection of previous experiences with regard to career-related skills and interests. The findings from the potential analysis can also help students to select the career fields that are most suitable for them for the subsequent practice-oriented career orientation days. Each potential analysis includes an introduction, an assessment of the current situation, various types of tasks and intensive self-reflection.

Introduction to Potential Analysis

Understandable explanation for the students of the goals, processes and content of the potential analysis.

This enables them to understand what happens when and for what purpose. Through this understanding, they will understand the importance of the potential analysis for their own career orientation. The introduction also enables them to adapt to new tasks that are not typical for school.

Individual positioning

In this, small groups work out what each student already knows about themselves and their own strengths and what specific orientation they need. In this way, each participant starts the potential analysis with individual questions.

Central pedagogical task: Initiate and accompany reflection

The teachers accompany the students through all elements of the potential analysis with interest, appreciation and encouragement. They encourage the students to reflect on themselves and supplement their self-assessment with an appreciative external perspective. In this way, they support the students in breaking down critical self-assessments and drawing their own conclusions. In the final, comprehensive reflection discussion on the potential analysis, the planning perspective is also taken into account: Which findings are of particular relevance and what next steps can be derived from them?

Explore skills

All tasks in the potential analysis are designed to explore various job-relevant skills in a playful way.

Methodological skills: … are the ability to design and solve certain activities and tasks appropriately and successfully. These include, for example, work planning, creativity and problem-solving skills.

Personal skills: … are the ability to assess yourself, develop yourself and bring your own personality into the design of tasks. They are expressed, for example, in characteristics such as motivation, reliability or independence.

Social skills: … are expressed in the ability to shape social relationships cooperatively and constructively. These include, for example, teamwork, communication and conflict management skills.

Diverse methods and tasks

The potential analysis offers a broad mix of methods and tasks. Action-oriented tasks encourage the joy of trying things out. There are individual and group tasks of varying difficulty levels. Action-oriented task types include, for example, construction exercises or experiential learning exercises.

Exploring interests relevant to career choice

For this reason, the various tasks are linked to career orientation and the world of work. In addition, initial interests that are relevant for later career choices are addressed.

Conclusion: Reflect, secure results, agree on goals

At the end of the potential analysis, all experiences and results from the task phase are discussed in individual discussions. The educational specialists guide the conversation with reflection-provoking questions, provide strength-oriented feedback on their observations and support the young person in drawing their own conclusions. The reflection conversation ends with a joint formulation of goals in which the young person himself or herself states what he or she intends to do for his or her future career orientation. The findings from the potential analysis can also be helpful for the students in selecting the career fields that are right for them for the subsequent practice-oriented BO days and in approaching the BO days with a specific individual focus.

Quality standards for potential analysis

These are intended to help ensure and optimize the quality of the implementation of the potential analysis. They define the objectives, the content, and the organizational and pedagogical framework for successful potential analyses. It is particularly important for implementation that the exploration of competencies and interests within the scope of the potential analysis is carried out with a pedagogical objective. This also defines the attitude and task for the educational specialists.

Figure 13: Elements of the potential analysis process

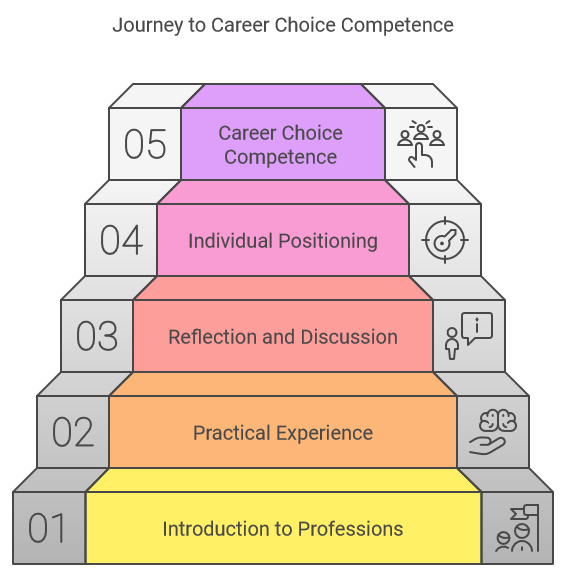

Instrument 2: Discover professions in the practice-oriented BO days

The practice-oriented BO days of the career orientation program do not take place in companies, but in inter-company vocational training centers (ÜBS) or comparable institutions. These offer an ideal learning environment with their training workshops.

Objective

The practical BO days are intended to help students acquire a bundle of specific skills and knowledge that can be summarized as “career choice competence.” This enables young people to shape their own career orientation with a view to personal interests and needs in such a way that they can later make a well-considered and well-founded career choice.

They receive a broad and varied overview of typical activities and challenges and what skills they need to master them. In direct connection with the practical testing, they reflect on which activities correspond to their personal skills and interests.

Space for reflection

The added value of the measures only comes from the combination of experience and reflection. Dialogue and reflection help students to draw individual conclusions for their future career orientation. Reflection takes place in the form of group discussions and individual discussions in all implementation phases of the career orientation program: at the start, during the course of the program and at the end. An individual one-on-one discussion following the career orientation days rounds off the entire career orientation measure. The next steps in career orientation are also taken into account.

Offer and selection of professional fields

Depending on the length of the practice-oriented BO days, the young people can try out two or more career fields. These fields do not refer to individual professions, but rather provide a comprehensive overview, because the young people should not commit to specific careers during this phase, but rather get to know the diversity of the professional world.

In order to ensure diversity, the educational providers’ offer to young people must include at least four professional fields. Each of the following four areas must be covered by at least one professional field:

1 Social work, care, health

2 Business and administration, transport and logistics, tourism and hospitality

3 Trade and technology, industry, natural sciences

4 Crafts

The young people should be given individual advice when choosing their career fields. On the one hand, this will be referred to in the reflection discussions after the potential analysis. On the other hand, the career fields will be presented in a suitable format before the practical BO days begin and the individual career fields will be considered together.

“Individual Positioning” – an exchange about career ideas

This takes place as a group discussion during the practice-oriented BO days at the provider, not beforehand. The exchange addresses career ideas and influencing factors that young people are often not aware of, but which may have a strong influence on their career choice – and which can also limit the range of possible paths. These factors include gender aspects, status issues or identity psychology factors. During the “individual positioning” assessment, students can define which personal questions and goals they will approach the practice-oriented BO days with.

Getting to know the selected professional fields

The young people try out activities and challenges in the world of work that are as realistic as possible. In doing so, they learn what job-related skills they need for this. They experience different company-typical processes, production and service processes.

All of this is embedded in a specific professional application that is designed by the provider and filled with many action-oriented tasks. In this way, the young people are placed in a scenario that could also exist in real working life. During implementation, important cross-cutting issues such as digitalization, Working World 4.0 and Green Working Environments should also be taken into account.

Practice-oriented BO days for different target groups

The practice-oriented BO days can be designed differently depending on the region, type of school and career orientation concept of a country, a school or an extracurricular learning location. It is important that the students are neither over- nor under-challenged. For example, offers for special schools should be designed differently than offers for high schools.

Figure 14: Relevant elements of the discovery of professions in the practice-oriented days

Practice Example: Implementation of BOP in SBH #

SBH – Promotion of career orientation in inter-company and comparable vocational training centres (BOP)

The program “Promoting career orientation in inter-company and comparable vocational training centres” (BOP) is aimed at students in secondary level I of general education schools. A potential analysis is supported, which usually takes place in the second half of grade 7, and the workshop days in grade 8. The potential analysis is intended to encourage students to deal with their “talents”, their already clear skills, but also the potential that is still “dormant” within them. The focus is on the personal experience: “I can do something!”, the fun of mastering challenges and the encouragement to (co-)design their own development. In action-oriented processes, participants are given the opportunity to try out their own skills and identify their own abilities, inclinations and interests. They learn to reflect on these in relation to initial cross-occupational requirements. They are motivated to deal with their own goals in their professional and private lives and to further develop their skills in the spirit of lifelong learning. The results of the potential analysis serve as the basis for subsequent individual support, which specifically supports the students in their skills development. The results provide initial indications of career inclinations. A career choice decision does not correspond to the development phase of this age group and is therefore expressly not intended at this time. At the end of a potential analysis, each student receives a certificate and a skills profile with detailed descriptions of support recommendations. The career choice pass is used as a documentation tool.

The subsequent workshop days help the young people to develop realistic ideas about the world of work and their own skills and interests. Career orientation also serves to enable a targeted selection of an internship that is tailored to the individual skills and interests of the students. We offer suitable equipment for meaningful career orientation in realistic work environments. The students complete practical work samples under the guidance of our pedagogically experienced trainers in various professional fields. The “Career orientation in inter-company and comparable vocational training centers” is funded by the Federal Ministry of Education and Research.

-

- Please watch appendix in chapter 12 for Magdeburg wbl-examples

Statements of partners #

Country: Portugal #

Institution: EPRALIMA_Escola professional do Alto Lima, CIPRL

Contact person: Célia Nunes

1. What forms of work-oriented learning exist as part of regular vocational education and training in the country?

At the Learning Place Company:

| Yes | No | |

| Apprenticeship | x | |

| Internship | x | |

| Company Visits | x | |

| Job Shadowing | x | |

| Other |

If other: Pl. explain:

Notes:

- Internship only exists in the context of Erasmus+ mobility projects for VET learners. It is not part of the regular component of the VET courses.

- Job shadowing only exists to staff (VET trainers and VET professionals), not for VET learners. It is done in the context of Erasmus+ mobility projects. It is not part of the regular component of the VET courses.

At the Learning Place School:

| Yes | No | |

| Workshops | x | |

| Laboratories | x | |

| Virtual (student) company | x | |

| Other |

If other: Pl. explain:

2. Are existing forms of work-based learning taken into account in the current legal regulations?

If yes: pl. list with bullet points

Yes, the programme of the VET courses has a component of work-based learning (apprenticeship). This component is mandatory because it is part of the VET course.

https://catalogo.anqep.gov.pt/

3. What sources of funding exist to ensure forms of work-based learning (as indicated under point 1)?

| Government / Public sources | x |

| Companies | |

| Students / Parents | |

| Mixed forms |

If mixed forms: please explain

4. Is work-based learning part of the pedagogical training and continuing education of teaching staff?

| Yes | No | |

| Teaching staff of vocational schools | x | |

| Teaching staff of companies | ||